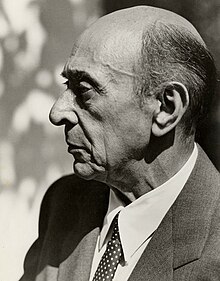

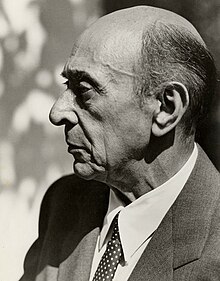

Expressionism as a musical genre is notoriously difficult to exactly define. It is, however, one of the most important movements of 20th Century music. The central figures of musical expressionism are Arnold Schoenberg and his pupils, Anton Webern and Alban Berg, the so-called Second Viennese School. The expressionist period can be associated loosely with Schoenberg's atonal period, which can be found after he finally rejected tonality, but before he began composing according to the twelve-tone technique, although the extent to which clear divisions between periods can be made is debatable.

Roughly speaking, musical expressionism can be said to begin with Schoenberg's Second String Quartet (written 1907-08) in which each of the four movements gets progressively less tonal. The third movement is arguable atonal and the introduction to the finale is very chromatic, arguably has no tonal centre, and features a soprano singing "Ich fühle Luft von anderem Planeten" ("I feel the air of another planet"), taken from a poem by Stefan George. This may be representative of Schoenberg entering the 'new world' of atonality. Alban Berg

In 1909, Schoenberg composed the one act 'monodrama' Erwartung. This is a thirty minute, highly expressionist work in which atonal music accompanies a musical drama centred around a nameless woman. Having stumbled through a disturbing forest, trying to find her lover, she reaches open countryside. She stumbles across the corpse of her lover near the house of another woman, and from that point on the drama is purely psychological: the woman denies what she sees and then worries that it was she who killed him.

The plot is entirely played out from the subjective point of view of the woman, the audience is never able to get an objective viewpoint. Furthermore, the emotional distress of the woman is reflected in the music; this might be compared to the aesthetic of Edvard Munch's The Scream, in which the surrounding landscape is affected by the scream of the protagonist. This inter-disciplinary comparison is representative of the inter-disciplinary nature of expressionism; it is a genre that is found in literature and in painting. The plot to Erwartung has some grounding in reality in the true story of the lunatic Anna O. (real name Bertha Pappenheim). The libretto was written by her sister, Marie: an expression of her own anguish perhaps? These three features (subjectivity, the aesthetic of the 'scream', and an expression of real life hardship, are all characteristic features of other musical expressionist works.

In 1909, Schoenberg completed the Five Orchestral Pieces. These were constructed freely, based upon the subconscious will, unmediated by the conscious, anticipating the main shared ideal of the composer's relationship with the painter Wassily Kandinsky. As such, the works attempt to avoid a recognisable form, although the extent to which they achieve this is debatable.

Between 1908-1913, Schoenberg was also working on a musical drama, Die Glückliche Hand. The music is again atonal. The plot begins with an unnamed man, cowered in the centre of the stage with a beast upon his back. The man's wife has left him for another man; he is in anguish. She attempts to return to him, but in his pain he does not see her. Then, to prove himself, the man goes to a forge, and in a strangely Wagnerian scene (although not musically), forges a masterpiece, even with the other blacksmiths showing aggression towards him. The woman returns, and the man implores her to stay with him, but she kicks a rock upon him, and the final image of the act is of the man once again cowered with the beast upon his back.

This plot is highly symbolic, written as it was by Schoenberg himself, at around the time when his wife had left him for a short while for the painter Richard Gerstl. Though by the time Schoenberg began the work, she had returned, their relationship was far from easy. The central forging scene is seen as representative of Schoenberg's disappointment at the negative popular reaction to his works. His desire was to create a masterpiece, as the protagonist does. Once again, Schoenberg is expressing his real life difficulties.

At around 1911, the painter Wassily Kandinsky wrote a letter to Schoenberg, which initiated a long lasting friendship and working relationship. The two artists shared a similar viewpoint, that art should express the subconscious (the 'inner necessity') unfettered by the conscious. Kandinsky's Concerning The Spiritual In Art (1914) expounds this view. The two exchanged their own paintings with each other, and Schoenberg contributed articles to Kandinsky's publication Der Blaue Reiter. This inter-disciplinary relationship is perhaps the most important relationship in musical expressionism, other than that between the members of the Second Viennese School.

The inter-disciplinary nature of expressionism found an outlet in Schoenberg's paintings, encouraged by Kandinsky. An example is the self portrait Red Gaze (see [1]), in which the red eyes are the window to Schoenberg's subconscious.

Webern's music was close in style to Schoenberg's expressionism for only a short while, c. 1909-13. His Five Pieces for Orchestra, Op. 10 (1911-13) are an example of his expressionist output, and might be compared to Schoenberg's Five Orchestral Pieces, Op. 16, composed 1909.

Berg's contribution includes his Op. 1 Piano Sonata, and the Four Songs of Op. 2. His major contribution to the genre, however, is the opera Wozzeck, composed between 1914-25, a very late addition to the genre. The opera is highly expressionist in subject material in that it expresses mental anguish and suffering and is not objective, presented, as it is, largely from Wozzeck's point of view, but it presents this expressionism within a cleverly constructed form. The opera is divided into three acts, the first of which serves as an exposition of characters. The second develops the plot, while the third is a series of musical variations (upon a rhythm, or a key for example). Berg unashamedly uses sonata form in one scene in the second act, describing himself how the first subject represents Marie (Wozzeck's mistress), while the second subject coincides with the entry of Wozzeck himself. This heightens the immediacy and intelligibility of the plot, but is somewhat contradictory with the ideals of Schoenberg's expressionism, which seeks to express musically the subconscious unmediated by the conscious. While Wozzeck helped to popularise the genre, it did so at the expense of the ideals.

Indeed, by the time Wozzeck was performed in 1925, Schoenberg had introduced his twelve-tone technique to his pupils, representing the end of his expressionist period (in 1923).

As such, musical expressionism can be said to be chiefly centred upon the ideas and work of Arnold Schoenberg (1907-1923), although Berg and Webern did also contribute significantly to the genre. It was a significant, if not altogether popular style, and some of its influences can be seen in Béla Bartók's opera Bluebeard's Castle (1911), with its emphasis on psychological drama represented in music.

Much like impressionism, expressionism is a term that was first used in connection with painting. In many aspects, it is the direct opposite of impressionism. Unlike impressionism, its goals were not to create passive impressions and moods, but to strongly express (hence the name) intense feelings and emotions.

Expression is actually pretty difficult to describe. You could say that it is somewhat like romanticism because they both seek to portray the composer's emotions. The main difference is that expressionism puts the emotional expression above everything else. While romantics (such as Robert Schumann or Johannes Brahms) also showed emotion in their music, they did so while still following traditional methods of writing music. On the other side, expressionists completely ignored tradition and focused on expressing emotions at all costs. For this reason, expressionistic music is often dissonant, fragmented, and densely written.

Pierrot Lunaire by Arnold Schoenberg... journey inside the mind of the composer

To put it another way, let's compare it once more to impressionism. You could say that an impressionist work portrays what is in the world around the composer: it creates an impression of what is being seen. An expressionist work, on the other hand, portrays what is going on inside the composer's mind: it is an expression of what is being felt. The example we've provided here is the beginning of Pierrot Lunaire, by Arnold Schöenberg. Notice how it's not like much of the music you're probably used to hearing.

Three major expressionist composers are Schöenberg, Alban Berg, and Paul Hindemith.